The Sa’wkele, The Ku-Ku, The Boqta, The Henin: How the Mongol Occupation of Europe Changed European Women’s Fashion Forever

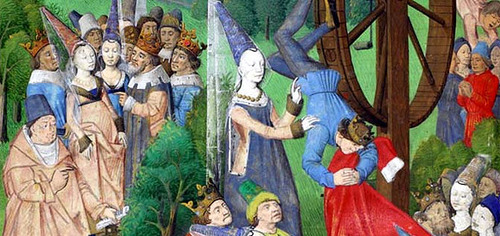

One of the most immediately recognizable symbols of the European Middle Ages is the towering, often conical or cylindrical, women’s headdresses popular throughout Europe in the 15th century. To this day, the tall, often veil-decorated “Princess Hat” is immediately known even to American children as a sign of feminine stature, nobility, and elegance. Tiny, cheap versions of this hat are sold to women and little girls by the millions at Renaissance Faires, theme parks, costume shops, and carnivals all over the United States. They look something like this:

In just about every American imagination, nothing is more essentially European than the elaborate, gravity-defying tall headdress or henin worn by the noblest women of history. Indeed, the European Henin is synonymous to many Americans as a visual symbol of frail feminity, “Faire Maydens”, milky complexions and delicate white women who must be protected by knights, preferably in shining armor.

(psst. notice people of color in this miniature from Boccaccio’s The Fall of Princes: more on that in later posts)

But what if I told you the heads this historical hat truly belongs on are not only those of women of color, but unrivaled Warrior Queens who ruled a vast empire, went to war with infant sons strapped to their backs, and commanded armies of tens of thousands?

There is something that not even doctorate-holding Western Medievalists and Medieval Fashion experts will tell you, and may not even be aware of: The Henin did not spring out of nothingness to adorn the heads of European noblewomen.

The European Henin is modeled directly after the willow-withe and felt Boqta (Ku-Ku) of Mongolian Queens, which could reach over five to seven feet in height.

Mongolian women’s boqta also had a special role: because men and women’s clothing were more or less exactly the same in design, appearance and function, reflecting thousands of years of more or less equal rights between the genders, the women’s tall headdresses served to differentiate men and women from a distance.

Mongolian equestrian culture influenced fashion as well as martial technology: the headdresses would have been even more impressive on horseback. The higher a woman’s position, the taller, richer, and more elaborately decorated the headdress.

The important cultural role of the headdress is elaborated upon in Weatherford’s Secret History of the Mongol Queens, in this portion about the warrior Queen Maduhai as she prepares to lead her soldiers to war:

The chronicles all agree that she fixed her hair to accommodate her quiver. The hairstyle of noble married women of that era precluded fighting or any other manual endeavor. She removed the headdress of peace and put on her helmet for war.

By taking off her queenly headdress, known as the boqta, she removed virtually the only piece of clothing that separated a man from a woman. The boqta ranks as one of the most ostentatious headdresses of history, but it had been highly treasured by noble Mongol women since the founding of the empire.* The head structure of willow branches, covered with green felt, rose in a narrow column three to four feet high, gradually changing from a round base to a square top…The higher the rank, the more elaborate the boqta, and as a queen, Mandhui would have worn a highly elaborate one. A variety of decorative items such as peacock or mallard feathers adorned the top with a loose attachment that kept them upright but allowed them to flutter high above the woman’s head.

The contraption struck many foreign visitors as odd**, but the Mongol Empire had enjoyed such prestige that medieval women of Europe imitated it with the hennin, a large cone-shaped headdress that sat towards the back of the head rather than rising straight up from it as among the Mongols. With no good source of peacock feathers, European noblewomen generally substituted gauzy streamers flowing in the wind at the top.

* The ebook preview is truncated. I happen to own the book and have typed out the rest of the passage from hard copy.

** This statement reflects the bias of the author (Weatherford)-foreign visitors found the boqta overwhelmingly impressive statements of wealth. For primary source description contemporaneous with women in the boqta (c. the 1200s), keep reading below the cut!

FULL HISTORY OF THE BOQTA, MORE PHOTOS AND LINKS BELOW THE CUT!

Holy shit. My mind has been blown.

Is there ANYTHING the Europeans did not take from other cultures?